Today marks exactly two years until the next NSW State election (scheduled for Saturday 23 March, 2019).

Despite the fact we are half-way through it, there has been a distinct lack of progress on policy and law reform issues that affect NSW’s lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex (LGBTI) communities during the current term of Parliament.

This is in marked contrast to the previous term – which saw the abolition of the homosexual advance defence (or ‘gay panic’ defence), as well as the establishment of a framework to expunge historical convictions for gay sex offences.

The parliamentary term before that was even more productive, with a suite of measures for rainbow families (including the recognition of lesbian co-parents, equal access to assisted reproductive technology and altruistic surrogacy, and the introduction of same-sex adoption) as well as the establishment of the registered relationships scheme.

With a (relatively) new Premier in Gladys Berejiklian, now is the time for the Liberal-National Government specifically, and the NSW Parliament generally, to take action to remedy their disappointing recent lack of activity.

Here are 12 issues, in no particular order, which I believe need to be addressed as a matter of priority – and if Premier Berejiklian won’t fix them in the next 24 months, then they must be on the agenda of whoever forms government in March 2019.

**********

The first four issues relate to the state’s fundamentally broken anti-discrimination laws, with the Anti-Discrimination Act 1977 now one of, if not, the worst LGBTI anti-discrimination regime in the country[i].

- Include bisexual people in anti-discrimination laws

NSW was actually the first jurisdiction in Australia to introduce anti-discrimination protections on the basis of homosexuality, in 1982.

However, 35 years later and these laws still do not cover bisexuality – meaning bisexual people do not have legal protection against discrimination under state law (although, since 2013, they have enjoyed some protections under the Commonwealth Sex Discrimination Act 1984).

NSW is the only state or territory where bisexuality is excluded. This is a gross omission, and one that the NSW Parliament must rectify urgently.

- Include intersex people in anti-discrimination laws

The historic 2013 reforms to the Commonwealth Sex Discrimination Act 1984 also meant that Australia was one of the first jurisdictions in the world to provide explicit anti-discrimination protection to people with intersex traits.

Since then, Tasmania, the ACT and more recently South Australia have all included intersex people in their respective anti-discrimination laws. It is time for other jurisdictions to catch up, and that includes NSW.

- Remove excessive and unjustified religious exceptions

The NSW Anti-Discrimination Act 1977 also has the broadest ‘religious exceptions’ in the country. These legal loopholes allow religious organisations to discriminate against lesbian, gay and trans people in a wide variety of circumstances, and even where the organisation itself is in receipt of state or Commonwealth money.

The most egregious of these loopholes allow all ‘private educational authorities’, including non-religious schools and colleges, to discriminate against lesbian, gay and trans teachers and students.

There is absolutely no justification for a school – any school, religious and non-religious alike – to be able to fire a teacher, or expel a student, on the basis of their sexual orientation or gender identity.

All religious exceptions, including those exceptions applying to ‘private educational authorities’, should be abolished beyond those which allow a religious body to appoint ministers of religion or conduct religious ceremonies.

- Reform anti-vilification offences

NSW is one of only four Australian jurisdictions that provide anti-vilification protections to any part of the LGBTI community. But the relevant provisions of the Anti-Discrimination Act 1977 are flawed in two key ways:

- As with anti-discrimination (described above), they do not cover bisexual or intersex people, and

- The maximum fine for a first time offence of homosexual or transgender vilification is lower than the maximum fine for racial or HIV/AIDS vilification.

There is no legitimate reason why racial vilification should be considered more serious than anti-LGBTI vilification so, at the same time as adding bisexuality and intersex status to these provisions, the penalties that apply must also be harmonised.

**********

The following are four equally important law reform and policy issues for the state:

- Reform access to identity documentation for trans people

The current process for transgender people to access new identity documentation in NSW – which requires them to first undergo irreversible sex affirmation surgical procedures – is inappropriate for a number of reasons.

This includes the fact it is overly-onerous (including imposing financial and other barriers), and makes an issue that should be one of personal identification into a medical one. It also excludes trans people who do not wish to undergo surgical interventions, and does not provide a process to recognise the identities of non-binary gender diverse people.

As suggested in the Member for Sydney Alex Greenwich’s Discussion Paper on this subject[ii], the process should be a simple one, whereby individuals can change their birth certificates and other documentation via statutory declaration, without the need for medical interference.

At the same time, the requirement for married persons to divorce prior to obtaining new identity documentation (ie ‘forced trans divorce’) should also be abolished.

- Ban involuntary sterilisation of intersex infants

One of the major human rights abuses occurring in Australia today – not just within the LGBTI community, but across all communities – is the ongoing practice of involuntary, and unnecessary, surgical interventions on intersex children.

Usually performed for entirely ‘cosmetic’ reasons – to impose a binary sex on a non-binary body – this is nothing short of child abuse. People born with intersex characteristics should be able to make relevant medical decisions for themselves, rather than have procedures, and agendas, imposed upon them.

The NSW Government has a role to play in helping to end this practice within state borders, although ultimately the involuntary sterilisation of intersex infants must also be banned nation-wide.

- Ban gay conversion therapy

Another harmful practice that needs to be stamped out is ‘gay conversion therapy’ (sometimes described as ‘ex-gay therapy’).

While thankfully less common that it used to be, this practice – which preys on young and other vulnerable LGBT people who are struggling with their sexual orientation or gender identity, and uses pseudo-science and coercion in an attempt to make them ‘straight’/cisgender – continues today.

There is absolutely no evidence that it works, and plenty of evidence that it constitutes extreme psychological abuse, often causing or exacerbating mental health issues such as depression.

There are multiple policy options to address this problem; my own preference would be to make both the advertising, and provision, of ‘conversion therapy’ criminal offences. Where this targets people aged under 18, the offence would be aggravated, attracting a higher penalty (and possible imprisonment)[iii].

- Improve the Relationship Register

As Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull and his Liberal-National Government continue to dither on marriage equality (despite it being both the right thing to do, and overwhelmingly popular), in NSW the primary means to formalise a same-sex relationship remains the relationships register.

However, there are two main problems with the ‘register’ as it currently stands:

- Nomenclature: The term ‘registered relationship’ is unappealing, and fails to reflect the fundamental nature of the relationship that it purports to describe. I believe it should be replaced with Queensland’s adopted term: civil partnership.

- Lack of ceremony. The NSW relationship register also does not provide the option to create a registered relationship/civil partnership via a formally-recognised ceremony. This should also be rectified.

Fortunately, the five-year review of the NSW Relationships Register Act 2010 was conducted at the start of last year[iv], meaning this issue should already be on the Government’s radar. Unfortunately, more than 12 months later no progress appears to have been made.

**********

The following two issues relate to the need to ensure education is LGBTI-inclusive:

- Expand the Safe Schools program

Despite the controversy, stirred up by the homophobic troika of the Australian Christian Lobby, The Australian newspaper and right-wing extremists within the Commonwealth Government, Safe Schools remains at its core an essential anti-bullying program designed to protect vulnerable LGBTI students from harassment and abuse.

Whereas the Victorian Government has decided to fund the program itself, and aims to roll it out to all government secondary schools, in NSW the implementation of Safe Schools has been patchy at best, with limited take-up, and future funding in extreme doubt.

Whatever the program is called – Safe Schools, Proud Schools (which was a previous NSW initiative) or something else – there is an ongoing need for an anti-bullying program to specifically promote the inclusion of LGBTI students in all NSW schools, and not just those schools who put their hands up to participate.

- Ensure the PDHPE curriculum includes LGBTI content

Contrary to what Lyle Shelton et al might believe, the LGBTI agenda for schools goes far beyond just Safe Schools. There is also a need to ensure the curriculum includes content that is relevant for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex students.

One of the key documents that should include this information is the Personal Development, Health and Physical Education (PDHPE) curriculum.

The NSW Education Standards Authority is currently preparing a new K-10 PDHPE curriculum. Unfortunately, it does not appear to be genuinely-inclusive of LGBTI students, with only one reference to LGBTI issues (conveniently, all in the same paragraph, on the same page), and inadequate definitions of sexuality/sexual orientation.

Fortunately, there is an opportunity to make a submission to the consultation process: full details here. But, irrespective of what the Education Standards Authority recommends, if the PDHPE curriculum does not appropriately include LGBTI students and content, then the Parliament has a responsibility to step in to ensure it is fixed.

**********

The final two issues do not involve policy or law reform, but do feature ‘borrowing’ ideas from our colleagues south of the Murray River:

- Appoint an LGBTI Commissioner

The appointment of Rowena Allen as Victorian Commissioner for Gender and Sexuality appears to have been a major success, bringing together LGBTI policy oversight in a central point whilst also ensuring that LGBTI inclusion is made a priority across all Government departments and agencies.

I believe NSW should adopt a similar model, appointing an LGBTI Commissioner (possibly within the NSW Department of Premier and Cabinet), supported by an equality policy unit, and facilitating LGBTI community representative panels on (at a minimum) health, education and law/justice.

- Create a Pride Centre

Another promising Victorian initiative has been the decision to fund and establish a ‘Pride Centre’, as a focal point for the LGBTI community, and future home for several LGBTI community organisations (with the announcement, just last week, that it will be located in St Kilda).

If it acted quickly, the NSW Government could acquire the T2 Building in Taylor Square – just metres from where the 1st Sydney Gay Mardi Gras Parade started in June 1978 – before it is sold off by the City of Sydney. This is an opportunity to use this historic site for purposes that benefit the LGBTI community, and including the possible housing of an LGBTI Museum and/or exhibition space.

**********

This is obviously not an exhaustive list. I’m sure there are issues I have forgotten (sorry), and I’m equally sure that readers of this blog will be able to suggest plenty of additional items (please leave your ideas in the comments below).

But the most important point is that, if we are going to achieve LGBTI policy and law reform in the remaining two years of this parliamentary term, we need to be articulating what that agenda looks like.

And, just as importantly, if we want to achieve our remaining policy goals in the subsequent term – from 2019 to 2023 – then, with only two years left until the next election, we must be putting forward our demands now.

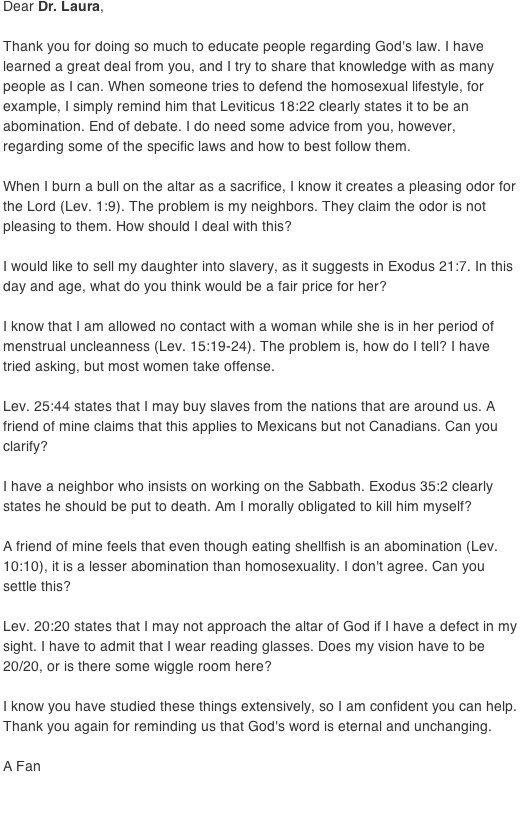

NSW Premier Gladys Berejiklian at the recent Sydney Gay & Lesbian Mardi Gras Parade. It’s time to back up this symbolic display of support with progress on policies and law reform.

Footnotes:

[i] For more, see What’s Wrong With the NSW Anti-Discrimination Act 1977.

[ii] See my submission to that consultation, here: Submission to Alex Greenwich Discussion Paper re Removing Surgical Requirement for Changes to Birth Certificate.

[iii] For more on both of the last two topics – intersex sterilization, and gay conversion therapy – see my Submission to NSW Parliament Inquiry into False or Misleading Health Practices re Ex-Gay Therapy and Intersex Sterilisation.

[iv] See my submission to that review, here: Submission to Review of NSW Relationships Register Act 2010.