[Content warning: homophobia; violence; suicidal ideation]

Those eyelashes.

He had beautiful blue eyes, scruffy blond hair and a mischievous smile, but it’s his eyelashes I remember most more than a quarter of a century later.

The day before, my Mum had driven me the eight hours from the farm west of Rockhampton where I was raised, to this boarding school in Brisbane’s inner-west. The day after I would start year 8, and what would be the longest five years of my life.

But that January afternoon, as the new boarders got to know each other down at the pool, I was transfixed by his eyelashes, droplets of water on them glistening in the Queensland summer sun.

That moment crystallised the feelings of difference that had slowly accumulated over the previous few years. At 10 and 11, I had grown increasingly bewildered as the other boys and girls at Blackwater primary began to express interest in each other.

At 12, in this unfamiliar environment, a long, long way from home, I finally understood why.

I liked boys.

**********

It took me another month or so to learn the right language to describe who I was. But I realised quickly afterwards that being gay was unlikely to be welcomed. Not by my National Party-voting parents (my Dad had actually nominated for federal pre-selection the year before). Not by my classmates. And definitely not by my school.

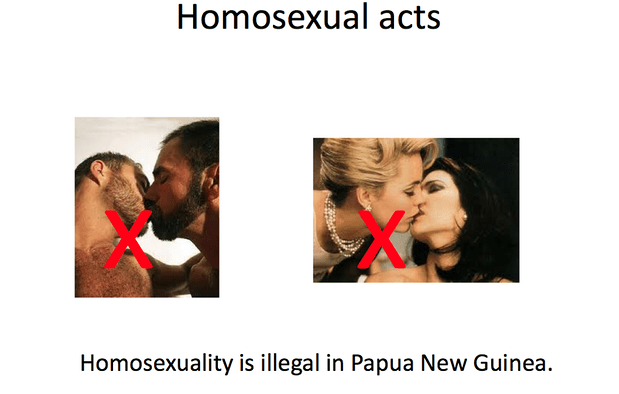

This was 1991. Homosexuality in Queensland had only just been decriminalised – and even then, the Parliament had imposed an unequal age of consent for anal intercourse (to ‘protect’ boys from being recruited to the homosexual lifestyle), something that would not be repealed until 2016.

Social attitudes were changing, but at a glacial pace. Many parts of the state were still firmly stuck in the Joh Bjelke-Petersen era. My school was one of them.

Based on the Lutheran faith, it enforced both religious indoctrination, and homophobia, with steely German efficiency.

We had chapel five times a week (Mondays, Tuesdays, Thursdays, Fridays, and an hour-plus every Sunday), and bible studies another two or three times.

The school rules, which were printed in the student diary, were based on supposedly ‘christian’ principles, and included the statement that homosexuality would not be tolerated because it was not in accordance with god’s will.

The sex education that was provided was a superficial, hetero-normative joke. While the jokes made by my classmates, often within earshot of unresponsive staff, were frequently homophobic.

If I was going to survive here, I would have to suppress my burgeoning same-sex attraction with all my might.

**********

It is hard, even now, especially now, to find the words to describe the utter loneliness of what followed.

Being surrounded 24/7 by 180 other boys, at a school of 1600 students overall, but having absolutely no-one to talk to, or confide in.

Needless to say there were no ‘out’ role models to look up to.

So, I quickly cut myself off, socially and emotionally, rather than risk the ostracism – or worse – of letting slip my secret.

Looking back, it was probably the only rational course of action. But it would slowly erode, and corrode, my self-esteem.

**********

I became so withdrawn that the rest of year 8, and most of year 9, was a numb blur.

As an academic child – some (well, if I’m being honest, most) might say nerd – I concentrated on my schoolwork.

The only snippets I learnt about what it meant to be gay came from pop-culture.

Sneaking peaks at Outrage magazine at the newsagent between school and the local shopping centre.

Scanning newspapers for any gay references I could find. One article about homosexuality from The Australian, back when it actually did journalism, sticks out in my mind, at least in part because of the scantily clad male torso it featured.

Trying to stay up late in the dorm to watch Sex with Sophie Lee, and Melrose Place featuring Matt the (largely-sexless) gay social worker.

Not exactly the most well-rounded education on ‘gayness’, but I devoured any morsel I could get.

**********

My clearest memory of year 9 came one evening during our allocated study period, during which each boarding house year group was supervised by a year 12 student.

This particular night our allocated ‘senior’ was joined by his twin brother and their friend, and they proceeded to discuss, in front of us, what they had got up to during the previous weekend.

On the Saturday night they and some others had apparently gone to a major bridge in Brisbane, found a toilet block where ‘faggots’ (their word, not mine) congregated, and ‘rolled’ them.

They were confessing to gay-bashing. Except this was no ordinary confession. They were smiling. Joking. Laughing. They were bragging.

Long before the term ‘toxic masculinity’ was popularised, I was learning what it meant, face-to-face.

I could not be 100 per cent certain whether what they were saying was true, or just teenage ‘bravado’ (even if it was the opposite of real bravery).

But I was now absolutely sure of one thing. Being gay at this school would not just lead to social exclusion, and possible expulsion. Being gay here was physically dangerous too.

I retreated even further into my closet. It became my whole world.

**********

Unsurprisingly, denying who I was, and isolating myself from my surrounds, was profoundly damaging to my mental health.

I suffered what I would later understand was major depression.

By the second term of year 8, I was already contemplating what seemed like the only way out: ending my life.

At first these thoughts came weekly. Then every few days.

By the start of year 10, I was thinking of killing myself upwards of a dozen times every 24 hours.

There wasn’t a day from then until after I finished year 12 that I didn’t think of committing suicide.

**********

Amidst the gloom, year 10 provided the one enjoyable term of my entire five-year stint of boarding school.

That was an eight-week ‘outdoor education’ program, where each class of about 30 lived in spartan accommodation in the hills north of Toowoomba.

By spartan, I really mean it. No flushing toilets. No running water full stop. To have a hot shower you had to build the fire, and boil the water, yourself. And after all that it only lasted for a total of about 30 seconds.

Still, there was something enjoyable about having no classes, and being immersed in an environment where kids could just be kids for a bit. I finally managed to make a few friends, mostly among the female students, something that would come in handy during the remaining two and a half years of hell in that school.

**********

Even out there, however, we couldn’t fully escape the religious inculcation the school was so expert in. We still had group daily prayer. And church every Sunday.

As part of its stereotypically ‘protestant’ emphasis on self-reliance, towards the end of the eight weeks we were also made to do a 24- or 48-hour ‘solo’, where we were left in the middle of the bush, with little other than a flashlight and a bible for company.

So I read it, cover to cover, in the desperate hope I might find something in there to help me overcome my predicament.

Which began a period of about 6 months where I would engage in an individual nightly prayer, wishing I would wake up as something other than myself. Each morning I was profoundly disappointed.

I was more lost than ever.

**********

The nadir of this search for ‘redemption’ came late in year 10, when I sought the assistance of one of the pastors to be baptised.

For a couple of months that involved spending an hour each week with him, discussing faith and what it meant to me.

We didn’t discuss homosexuality. I wasn’t going to raise it, and he certainly didn’t ask.

But it must been have clear to this kind old man (and that is still how I remember him) that the young boy in front of him was drowning.

If it was, then he himself was too far out of his depth to help.

My strongest memory of that entire process was sitting in his office, listening to – but not really hearing – his words, as it felt like my whole body dissolved into the couch, until I wasn’t there anymore.

It was clear that religion was not going to be my life-raft.

**********

Perhaps surprisingly, by year 11, things had slowly started to improve.

The friendships I had made with a few of the female day students strengthened. Even if I felt I couldn’t disclose my secret to them, just having someone, anyone, to talk to, even about random, meaningless stuff, made the days seem not so long, and the nights not quite so terrifyingly alone.

I was also learning more about this whole ‘gay’ thing.

One of the advantages of being a nerd meant I was free to visit, unsupervised, the University of Queensland Social Sciences Library, ostensibly to undertake research for my school assessments. In fact, I was becoming closely acquainted with the work of Alfred Kinsey and his ‘Sexual Behaviour in the Human Male’.

I surreptitiously picked up a few copies of Brother-Sister (the 90s, Brisbane equivalent of the Star Observer), reading them cover-to-cover and then throwing them away before heading back to campus.

It was reassuring to know that a gay world did exist out there, somewhere – a suburb, and a galaxy, removed from where I was.

Pop-culture was also steadily expanding its, and my, gayze. Tales of the City (the TV series) was an eye-opener, with its heady depiction of gay life in 70s San Francisco. It even made being gay look like it could be fun.

And I distinctly recall the moment I first saw the photos of Ian Roberts in Blue Magazine (images that were committed to memory for several years after that).

Life in the dorms even got slightly easier with the installation of shower curtains. Which, unless you’ve lived in a boarding house, may not seem like a big deal, but finally provided enough privacy to do what teenage boys do… A lot…

It felt like the invisible but ever-present weight I had been carrying was slowly lifting. There was much less ‘praying the gay away’, replaced with the almost imperceptibly small beginnings of self-acceptance.

**********

Any progress I had made was stopped in its tracks by a moment of brutality.

Well, two moments.

Physically, I had matured faster than some of my peers, and at 15 had a nascent patch of hair on my chest (which, I’ll be honest, I was a little bit chuffed about).

One evening early in year 11, after study a group of about half-a-dozen boys from my year ambushed me between two buildings, pinned me down and removed my shirt.

I struggled to break free, but there were too many of them.

I called out for help, which was then muffled by one of their hands across my mouth.

No-one came.

I didn’t comprehend what was going on, until one of them took out a razor and shaved my chest.

I think the whole thing was all over in about three minutes.

Looking back, I don’t know how but I somehow managed to compartmentalise this un-provoked attack. Pretending it didn’t mean anything. That it was ‘just’ some harmless hazing. That this kind of thing happened to everyone. Didn’t it?

Perversely, the dissociation of more than three years in the closet helped me to detach myself from this incident.

I tried to move on. I was even partially successful. Until it happened again.

**********

The second assault, towards the end of year 11, was much, much worse.

The modus operandi was similar – the shaving of my by-then slightly thicker thatch.

There were more people involved, this time at least a dozen, maybe 15 (including, sadly, my year 8 crush, the one with those ‘eyelashes’).

It happened in the dorm cubicle I shared with three other students, on the floor right next to my bed, stripping away any sense of safety it had previously provided.

The fact they came prepared with shaving cream, in addition to a razor, revealed just how pre-meditated it was.

I didn’t struggle. Or call out for help. The first attack had shown there was no point.

In fact, what sticks with me is just how quiet it was.

The sound of squeaky sneakers on the wooden floor. The whirr of the shaving cream. That’s all.

They didn’t even need to talk to each other. They knew what they were doing, having taken the school’s German efficiency and applied it to brutalising another student.

This was an act of dominance, and humiliation. I was confronted by my sheer powerlessness in comparison.

But the biggest psychological damage was inflicted by its mere repetition.

This was not, could not, be written off as simple ‘hazing’, lazily picking on outward physical difference.

Even if they didn’t express it – and I couldn’t say the words out loud – I knew they had worked out I was different in an inward, and far more significant way.

They were going to make me pay for it. I did. They had broken me.

**********

I didn’t report them. How could I? They constituted about a third of all the year 11 students in the boarding house. The popular boys. The rugby players. People who I continued to share a ‘home’ with, and see every morning, afternoon and evening of every single day.

I knew, without qualification, that if I complained, and any of them (or all of them) were punished as a result, the following 12 months would be living hell. The violence wouldn’t stop; it would escalate.

So I lowered my head.

I did confide in a couple of my female friends, Jo and Cindy. Who were rightly horrified and who, unbeknownst to me, reported the second incident to the school.

The school’s response was, to put it mildly, shocking.

They knew what had happened. And they knew exactly who had been involved. Nevertheless, they refused to take action unless I made a formal complaint – something which they must also have realised I couldn’t do, based on an entirely legitimate fear for my own safety.

We reached a stand-off.

The boarding house’s improvised approach was to take me out of study one night, and sit me alone on an uncomfortable chair in a fluorescently-lit corridor. They forced all of the boys who had been involved (thus conceding they knew exactly who did it) to come and apologise to me, one after another.

I don’t remember much of that experience. I certainly don’t recall any genuine contrition on their parts for the actual attack. Although I do remember several of them thanking me for not ‘dobbing’, and others apologising to me because they incorrectly thought that I had complained but now knew I hadn’t. Such were the warped moral priorities of the teenage male boarding student.

**********

About a week after those ‘nonpologies’, the school announced the student body leaders for the following year.

One of the boys who had assaulted me was named school captain.

Another was made head boarder.

If that wasn’t enough of a sick joke, because of my grades I was also named a prefect – and so would have to spend even more time alongside them.

**********

The icing on the cake of that almost unbelievably horrible year came a couple of weeks later.

As was the style at the time – but probably also as a reaction to what had happened to me – I had clippered my hair in a buzz cut.

Sitting in the back row of my Economics class, the teacher, who was also the ‘dean of student welfare’ for year 11, joked to the class, “didn’t you get enough of having your hair shaved in the boarding house, Alastair?”

**********

It was clear the school would never give a shit about me.

After four years in the closet, and beatings both physical and psychological, I barely cared about myself.

Which meant that year 12, for me, was simply a battle for survival.

The lowest point arrived in chapel one morning when, in front of years 11 and 12, a new pastor gave a sermon about a teenager from his previous parish.

The boy had come to see him, ‘confused’ about life and his place in it. The pastor claimed he had tried to help, but the boy ultimately took his life.

The pastor described how he was now in a better place, in a way that suggested this was not the worst thing the boy could have done in those circumstances.

That pastor had effectively ‘dog-whistled’ his insidious homophobia to a room full of 600 impressionable 15, 16 and 17 year-olds, intimating that they should consider killing themselves if they were confused.

Fortunately, my contrarian nature meant my immediate reaction was to think, “fuck you, I won’t do what you tell me”. It was possibly even the first day I believed I might eventually outlive that school.

But I often think about how the other 40 or 50 queer kids who were in chapel that morning reacted to his hate.

**********

The highest point of senior year came one August afternoon, as I sat in the office of my favourite English teacher, and the dean of student welfare for year 12, crying.

Yes, crying. Why was that a highlight? Because I had just committed the ultimate act of defiance in a school that was intent on erasing any student who happened to be gay or lesbian.

I had come out.

It almost goes without saying that it was the most difficult thing I had ever done. I was so emotionally spent afterwards that, even though Gayle was supportive (and wanted to help me attend a support group outside of school), I did not have sufficient energy left to take the next step. Or any steps.

Indeed, it would be another two years before I told another soul.

But it was enough that someone finally knew my secret.

It was also a pre-emptive act of remembrance. If I took my life in the weeks or months that followed, someone would know why. And they might be able to address the set of circumstances that contributed to it.

**********

The final term of year 12 was like the home straight of a marathon, as I limped and staggered towards the end. I literally had nothing left of myself to give.

Even my grades started to suffer (although I suspect Gayle encouraged some of the other teachers to give me special consideration).

But as I fell through the finish line tape, and started to maybe hope that the future could have something, anything, better to offer than the previous five years had mercilessly dispensed, the school had one last insult to add to my many injuries.

At the conclusion of each year in the boarding house, the senior students handed out ‘awards’ to the year 8, 9, 10 and 11 kids, while the year 11 students were given responsibility to dole out awards to the seniors.

Mine? In front of the entire boarding house, including staff, I had to walk up and collect the ‘Big Fat Poof’ award.

None of the staff intervened. All of the other kids laughed.

Those students had found the language to describe what the year 11s the year before – my classmates – had suspected. They saw right through me.

It almost seems appropriate my time at that wretched institution ended in one final act of humiliation before I walked out of its unwelcoming gates.

**********

A couple of days after final exams, my Dad drove me that same eight hour-trip back to my childhood farm in Central Queensland for the final time.

Sitting in the passenger seat, I was, in many ways, the same kid I had been five years prior. My physical age might have been 17, but emotionally I was only 12; specifically, that 12 year-old boy transfixed by those eyelashes, experiencing the exciting and confusing first throes of a teenage crush.

Except those subsequent years had stripped away any optimism I might have once held about the future, as my school and classmates collectively drummed into me that who I was was something to be ashamed of.

My teenage years had been stolen from me by religious indoctrination, and homophobia – which, at least in that environment, were very closely inter-twined.

I would have to ‘do over’ my adolescence, in the months and years to come. To make stupid mistakes, and learn from them. To grow up. To fall in – and out – of love.

Fortunately, the world outside would prove a far more accepting, and interesting, place than my boarding school had been.

It’s hard to imagine how it could have been any worse.

**********

Ten years later I found myself attending my school reunion on a rainy night in a dingy function room in the Valley.

You may ask why I would subject myself to that (and I certainly am as I write this) but, at the time, I felt like I had something to prove.

Unlike Romy, it wasn’t to show how successful or popular I was, merely to demonstrate that they hadn’t broken me. After everything they had put me through, I was still standing.

It wasn’t necessarily true. My personal life was basically a mess, and would be for another few years, right up until I met my fiancé Steve. But that wasn’t going to stop me from faking it.

Nevertheless, I am thankful I went for one reason. Early in the evening, one of the boys who had been involved in the second assault on me saw me through the crowd, made a beeline straight toward me, and unprompted offered me his apology for what he, and the others, had done.

Not only was it sincere, it was obvious the incident had weighed heavily on him in the decade since.

Nothing was going to take back what had happened. But it was comforting to hear the wrong acknowledged, and to know at least one of the perpetrators was genuinely remorseful.

**********

Another decade later I went to my school’s 20-year reunion on a sunny afternoon at a bowling club down by the Brisbane River.

This time I didn’t have anything to prove, but I did have something to gain – to reconnect with some of the friends I had made during my time there. Which I did, although once again the highlight was a pleasant surprise.

Mid-afternoon I found myself having a chat with the boy (well, now middle-aged man) with those ‘eyelashes’, as well as another student with whom I had shared a dorm cubicle all the way back in 1991.

The crush was long gone (what had I been thinking?). Instead, we had a lovely conversation about our lives and what we were up to. They offered their heart-felt congratulations on my engagement to Steve, even remarking that he was a ‘good-looking fella’ (well, I certainly think so).

It was all incredibly natural, and showed how much they had evolved in the intervening decades.

Indeed, we had all changed.

**********

Well, nearly all. While it had eventually got better for me, I was soon reminded that it didn’t get better for everyone.

I sat outside on the wooden steps leading down to the green chatting with another student from my year. After I told him about my relationship, he volunteered that he had been out on the gay scene during his twenties, but that he had since rediscovered Jesus and was now straight.

Worse still, he was employed by a faith-based organisation working with troubled youth on the streets. He was likely perpetuating the same harmful messages we had received, and subsequently contributed to him becoming ‘ex-gay’, inflicting them on another generation.

While I had somehow managed to survive that horrific school, and was living a beautiful life teenage Alastair scarcely would have dreamed possible, for him those same five years seemed to be stuck on repeat.

**********

For LGBTI people, if this post has raised issues for you, please contact QLife on 1800 184 527, or via webchat: https://qlife.org.au/

Or contact Lifeline Australia on 13 11 14.

At my grandma’s house, during a break between school terms.

Postscript: 19 April 2019

It is now just over a month since I shared this story. It’s fair to say it is the hardest thing I’ve ever written. But choosing to press publish was even harder. The response has been overwhelming. From friends who offered their love and support. I thank you from the bottom of my heart.

From others who shared their own, similar experiences. The countless tweets, and messages, saying that if you simply changed the date or location, their story mirrored mine. I thank you for your honesty, and honour your courage.

From people who I went to school with. Many of whom who wrote to say they wish they had known at the time, and could have done something to help (that’s one of the worst things about ‘the closet’, it isolates you from people who could be allies). I thank you for your support.

I have also received messages from other students who attended the same school, who’ve detailed their own shocking experiences of abuse and discrimination. Except for them the cause wasn’t homophobia, but racism. Which is not at all surprising – if an environment is toxic for one group, it’s highly likely to be toxic for others too. But it was still depressing to learn the horrors they endured. I thank you for your strength.

Just this week I received a message from one of the teachers at the school. Who expressed her sincerest sympathy about what had happened to me. In doing so, she confirmed one of the worst elements of the story: the pastor’s sermon. And she informed me that multiple teachers had told the school afterwards that it was unacceptable.

I’m thankful for that as well. Not just to know some of the teachers had tried to stand up for teenage me, and all the other queer kids who were there. But also because it was the part I had most trouble writing, and publishing. Ultimately, the version I included in the story was toned down from the reality – in truth, the pastor was much more explicit that gay kids should consider killing themselves.

While my recollection of what had happened was extremely vivid, the possibility that anyone would tell a chapel full of several hundred 15, 16 and 17 year olds that ending their life was a better outcome than being homosexual was so horrific that I doubted myself. I shouldn’t have.

Several people have asked why I wrote this story. The answer to that is complex. In part, it is an act of preservation, of making sure stories like mine are not forgotten. In another sense it has been about catharsis – it has been genuinely liberating to share these experiences publicly, and let go of them privately.

It is also an act of defiance. To let schools like mine know that mistreating kids just because they are gay, or lesbian, or bisexual, or trans, was not acceptable in Queensland in the 1990s. It’s not acceptable in Australia in 2019. And it won’t be acceptable in the future. Your religion has never been, is not, and will never be, justification for homophobia, transphobia or any other kind of prejudice.

That message is especially important now, as religious organisations desperately fight to retain their special privileges that allow them to discriminate against students, teachers and other staff solely on the basis of their sexual orientation and gender identity.

We must not let them get away with it. Because if we do, we’ll be reading stories like mine in 2043. And, most importantly, let’s never forget those stories we will never get to hear.

**********

Finally, if you have appreciated reading this article, please consider subscribing to receive future posts, via the right-hand scroll bar on the desktop version of this blog or near the bottom of the page on mobile. You can also follow me on twitter @alawriedejesus