One of the main cultural phenomena of 2013, at least from my perspective, was a welcome move towards telling the history of the HIV epidemic, and in particular looking back on the key years of the 1980s and early 1990s, especially in the US.

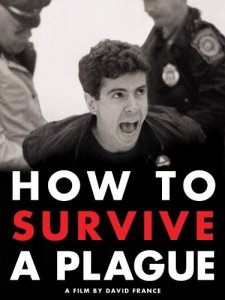

This started with the fantastic documentary How to Survive a Plague, directed by David France, focusing on the story of ACTUP activists in New York City. I wrote earlier in the year about how powerful this documentary was – almost 10 months later and I would still say this was the best, and most important, film I saw this year.

Which is not meant as any disrespect to the also rather wonderful All the Way Through Evening, directed by Australian Rohan Spong. This documentary presented a much more targeted examination of the impact of HIV, through the story of Mimi Stern-Wolfe, an incredible woman who, each year, organises a concert in New York which plays the music of composers lost to AIDS-related illness.

In theatre, I finally fulfilled a long-held ambition by seeing the Belvoir St revival of Angels in America: A Gay Fantasia on National Themes. Staged 20 years after Tony Kushner’s 2-part epic first debuted, director Eamon Flack, and indeed the entire cast, did a brilliant job of making the pain, and fear, and hope, and hopelessness, seem all too real (which is a pretty decent effort when the plays ask the audience to suspend their disbelief about angels suspended on ropes, or in this case, standing on stepladders).

It was also a privilege to see the 7-hour marathon (we saw Millenium Approaches and Perestroika back-to-back) with my fiancé Steven. Not normally a fan of theatre, he was as engrossed as I was by this production.

More importantly, these films and plays served as a ‘history lesson’ for both of us. Steven was born in December 1983, after the first deaths from AIDS-related illness in Australia. His entire life has been in the shadow of this epidemic. Even though I am (*cough*) a little bit older than that, I still turned 18 after saquinavir and ritonavir had been approved by the FDA in the US, fundamentally altering the nature of the epidemic for the better.

It feels right that all generations of gay and bisexual men, and indeed all people potentially affected by HIV, should take the time to reflect on the history of this epidemic. That we should remember the people who fought to overcome stigma and discrimination, who fought for better access to treatment, who fought for the right to survive.

And of course it is vital to remember the personal stories of those who lost their own fight.

But it is also vital that, in doing so, we do not lose sight of the challenges that remain. Because the activists of yesterday might be somewhat disappointed in us if we did not also fight the battles of today, and tomorrow, with the same conviction that they did.

This includes tackling the stigma and discrimination against people living with HIV that continues to exist in our society. And working hard to help prevent new transmissions – something that was thrown into sharp relief by recent figures which showed that HIV notifications increased 10% nationwide in 2012, including a jump of 24% in NSW.

Above all, the global challenge of HIV is in ensuring that all people have access to effective treatments, irrespective of their race, sexual orientation or gender identity, their class or their nationality. Cost should not be a barrier to receiving the latest drugs. Indeed, access to treatment must be considered a fundamental human right.

Hopefully, Australia can play its part in the reinvigoration of this fight as it hosts the AIDS 2014 conference in Melbourne next July.

In the meantime, the recent trend towards (re-)telling the history of HIV on stage and on film, which arguably started with We Were Here back in 2011 (about the impact of HIV on San Francisco), shows no signs of letting up.

Next month, Jean-Marc Vallee’s Dallas Buyers Club will hit our cinemas. It is reported that John and Tim, a documentary about the life of the author of the memoir Holding the Man, Timothy Conigrave, and his partner John Caleo, will also be released early in 2014. [Incidentally, that book was the first I read as a young gay man, and remains my favourite to this day].

Just this week, director Neil Armfield received Screen Australia funding to develop a film version of Holding the Man, based on Tommy Murphy’s 2007 stage adaptation. The Hollywood version of Larry Kramer’s largely autobiographical 1980s play The Normal Heart looks on track for a 2014 release, too.

Which, in a way, brings us all the way back to How to Survive a Plague. The scene of Kramer sitting in a room full of divided and dispirited activists, yelling “Plague!” is the one that has stayed with me above all others. One day, the epidemic that is the Human Immunodeficiency Virus will be over, in part because of the work of ACTUP activists and others like them. Til then, we must keep remembering, and keep fighting.

Related posts

My post after watching How to Survive a Plague: https://alastairlawrie.net/2013/02/23/how-to-survive-a-plague/

My post after watching Angels in America: https://alastairlawrie.net/2013/07/01/belvoir-st-theatres-angels-in-america/