I was never much of a country kid, despite growing up outside Blackwater, a couple of hours west of Rockhampton in Central Queensland.

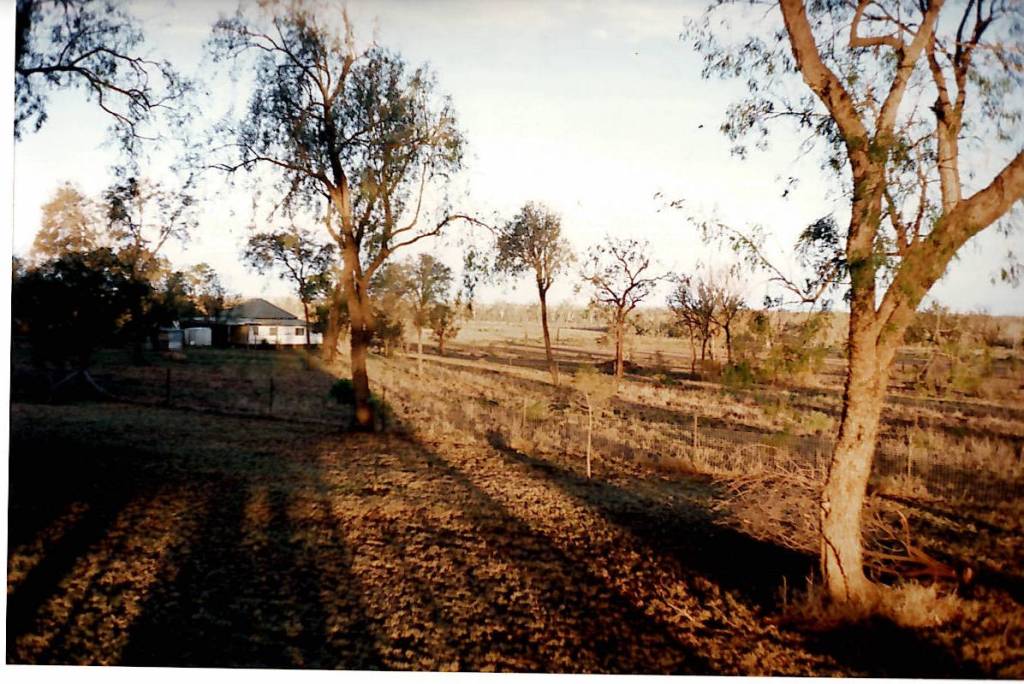

Our family lived on 16,000 acres of what I now know is Gangulu/Ghungalu land – a fact never mentioned in my Bjelke-Petersen-era classrooms.

My dad had about 2,000 head of cattle, and when it rained – which was not nearly often enough – planted crops on the most productive parts.

In my memories, the landscape appears mostly in brownscale. Brown grass, surrounded by more brown dirt. Brown Braford cattle, mustered with brown horses and cattle dogs. The grey-brown of kangaroos. The house gently brushed in a layer of fine, light-brown dust.

Even the other colours of the pastoral palette didn’t provide much contrast; the dull silver-green leaves of the brigalow scrub, and occasional fields of rust-brown sorghum or faded yellow wheat.

I admit, the picture I’m painting doesn’t sound particularly idyllic, but it wasn’t without its beauty either. The property didn’t need much rain to spring to life, and Burngrove Creek – which ran through its middle – in flood was always a spectacular sight. As was the dark outline of the Blackdown Tablelands, off to the distant south-east.

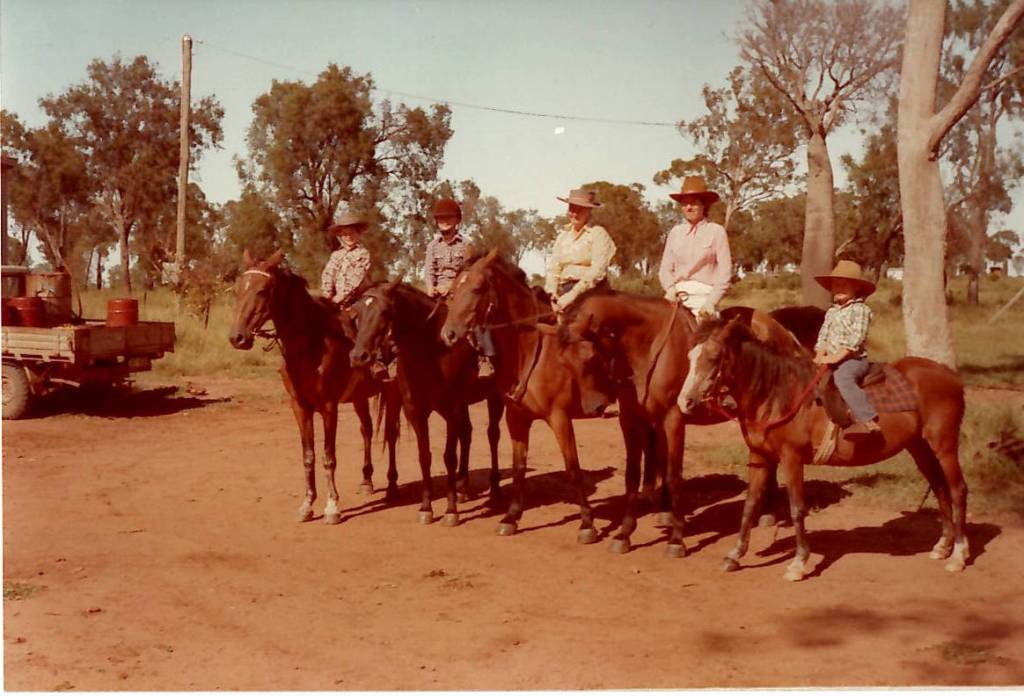

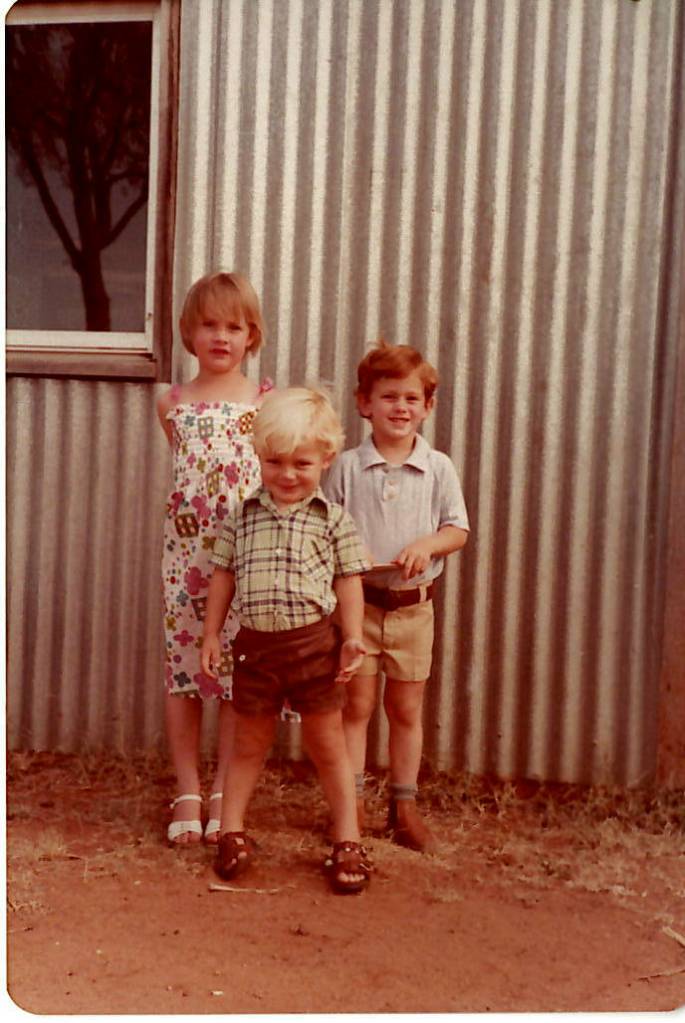

I was never much of a country kid, especially compared to my siblings. My older sister could easily have been described as a pony princess, while my older brother generally fulfilled the stereotype of the motorbike-riding, pig-shooting (and later rodeo-riding and ute-driving) son of the bush I was destined never to be.

I was much more of the nerdy and indoors-y child. I did have a horse, Spree (named by my mum, for reasons I’ve long since forgotten), but I wouldn’t have ridden it more than a handful of times. Which was still more frequently than I jumped on a motorbike: four wheels, once or twice; two wheels, never.

Nor did I contribute much toward the farm-work. Obviously, my mustering skills were close to non-existent, while my attempts at milking resulted in more frustration (both mine, and the cow’s) than milk.

I was put in charge of looking after the chooks, a responsibility I could at least handle: letting them out mid-afternoon, collecting the eggs, and then feeding them the scraps and locking them back up at dusk.

Once I learned to drive, I also sometimes ‘did the waters’ (driving around the property to check the dams, and troughs, to ensure the cattle had enough to drink). But that was it.

It was clear from an early age that farm-life just wasn’t for me – a feeling that only intensified as I got older.

And my parents accepted my reluctance, too. They never put pressure on me to do the things my siblings did, a freedom from expectation I largely took for granted when I was younger, but one I am deeply appreciative of as I look back now.

I was never much of a country kid, and the things I was actually interested in always seemed so far away. Theatre, and galleries, and crowds, and the alluring buzz of metropolitan, cosmopolitan life, were busy happening someplace else. Further than the ‘big smoke’ of Rocky, further even than Brisbane (although visiting Expo ’88 aged 10 gave a small taste of future possibilities, and yes I mean that non-ironically).

Blackwater instead had a run-down drive-in, one radio station, one commercial TV channel and, at least back then, little to stimulate an inquisitive, impatient mind.

Both push and pull factors were working together harmoniously to create the central truth of my growing up in country Australia: as soon as I could leave, I would.

I was never much of a country kid, although my partner Steve has often told me how jealous he is of what I got to experience.

The wide-open space. Being outdoors. The motorbikes. The animals, especially. The quiet. The freedom to simply be, away from other people. The charming country houses of my parents that he’s visited during our 13 years together.

Who knows, maybe he would have enjoyed my own youth much more than I did.

But then, like many people who grew up in the suburbs, I suspect he underestimates the challenges it posed.

The isolation.

The relentless sun (although being a bookish child had its advantages – as the only one in my family to make 40 without skin cancer).

The equally oppressive heat.

The reality animals were usually either productive (cattle, cows and chickens), or worked (horses and dogs). While the main childhood pet I had (a cat, Beethoven, which I shared with my brother) didn’t last long before being bitten by a snake.

The boredom.

The feeling of being apart, outside of the action.

The fact that for the first few years of my life the five of us lived in a couple of rooms, on slabs of concrete, down one end of a machinery shed.

It might be a cliché, but life on the land can be, often is, hard.

I was never much of a country kid, and that has been reflected in my choice of career. For at least a few generations, on both sides of my family, most men would grow up to be primary producers – mainly graziers, although there were also a cane farmer and mango and lychee grower among them.

While most of the women would work in a health-related field – with several nurses, including my mum, as well as an optometrist, a physio, and a speech pathologist.

My sister and brother both largely followed these well-worn paths: she, a vet, he – until recently – a grazier (although, perhaps in a sign of the times, he sold his own beef property and is now a full-time coal-miner).

It was far from inevitable I would become a public policy professional, working in several government departments and community sector organisations. Although once again my parents never made me feel a sense of obligation to stay on the land, and I thank them for the gift of being encouraged to follow my own track.

I was never much of a country kid. I only fired a gun once, when I was maybe 10 or 11 years old, under my dad’s strict supervision. It must have been apparent on my face just how little I enjoyed it. But I think he found the experience uncomfortable too.

In hindsight, I think it was one of the few times he did something because he thought it was the right thing for any child growing up on a farm to learn, rather than the right thing for his child, this particular child. We never spoke about it again.

I was never much of a country kid, but I think I inherited a lot from my dad. Not just the superficial – looks-wise I couldn’t be anyone other than his son, while I’ve commonly been mistaken for him over the phone.

Or characteristics like being softly-spoken and gentle (Steve has often commented he doesn’t understand how such a gentle-man survived more than half a century as a farmer).

More fundamentally, he imparted several of his core values.

Including the virtue of civic participation, and especially volunteerism. For him, that meant stepping in to fill in the gaps where governments failed to deliver essential services to rural communities, like being a long-time local fire warden.

And stepping up to advocate on behalf of his own community, by contributing via agricultural organisations like the United Graziers Association.

While my own LGBTI volunteering and advocacy is obviously driven by different goals and in service of a very different community, I’d like to think the urge to help, to make society better, as well as the way we both go about achieving that, are pretty similar.

I can also blame my dad for my life-long obsession with politics. The outlet for that obsession is far from shared – he unsuccessfully sought National Party pre-selection for the federal seat of Maranoa in 1990, as well as contesting, and losing, the state seat of Fitzroy in the Beattie-slide election of 2001, while I was previously a long-term member of the Labor Party, and even served as a ministerial adviser to the Rudd and Gillard Governments – but the ideal that politics is, or at least can be, a noble profession, is.

I was never much of a country kid, although it did teach me about silence – both the good and the terrible.

Like many such myths, behind the archetype of the ‘strong and silent’ man of the land lies a sliver of truth. In this case, for many farmers, my dad included, they would leave the house in the early morning, and try to do most of the demanding physical labour before the heat of the day’s middle. But a farm’s unending tasks cannot be ignored, keeping them occupied through to sunset when they finally return to the house. They might not speak to, let alone see, another human in daylight hours. For days on end.

These days – and especially working from home through the pandemic, which in my adult life has perhaps come closest to replicating that absence of day-to-day real inter-personal contact – I don’t consider my dad so much as reserved, as simply having fallen out of the habit of engaging with other people.

*****

There are some benefits to this physical dislocation. I’m grateful to my youth for the gift of an active inner-life, and strong inner-voice, attributes which come in handy in a now-socially distant, social media-driven world.

And for the innate sense of comfort in solitude, of doing everyday things on my own, something I know others, who grew up always being surrounded by people, often struggle with.

Inevitably, though, there are downsides as well. For me, these came in years 6 and 7 of primary school, when my sister and brother had already left for boarding school, with dad working on the farm and mum doing shift-work as a nurse at the same mine where my brother now works.

That period of engulfing, overwhelming, silence transformed an awkwardly, but conventionally, shy 10-year-old boy into a painfully introverted 12-year-old.

It left me completely unprepared to be transported several hundred kilometres away, to that same school in Brisbane as my siblings, a boarding house of hundreds, and school of more than 1,000 – with no privacy, or silence, for the next five years.

I constantly felt alone in that particular crowd.

I’m not sure that, having discovered I was same-gender attracted on my first day there (a long story for another time) and the school’s fervent, at times ferocious, homophobia, I was ever going to find much happiness in that toxic environment.

But I’m certain the lingering effects of that late-primary school drought in conversation, my under-developed communications skills and overly-honed ability to retreat into my thoughts, meant I started at a distinct disadvantage.

It would be many years before I would finally find the comfort of my own community, and a sense of home with others of my kind.

I was never much of a country kid, even if I inherited a lot from my mum too. She also grew up on a cattle property, which was even more isolated (on the Isaac River, south-west of Mackay).

Her father died when she was 13, however, and she eventually had to leave the land, moving to Mackay and looking after herself by becoming a nurse.

Those early hardships meant mum had to fight harder than dad for what she had. She learnt that sometimes help is not on its way, that you have to look after yourself.

And she developed a fearsome backbone – I was always much, much more scared of her than I was of dad.

The same was true for our (thankfully infrequent) arguments – she never backs down, a trait which I, as her youngest child, seem to take strongly after. It certainly makes dinner time discussion interesting.

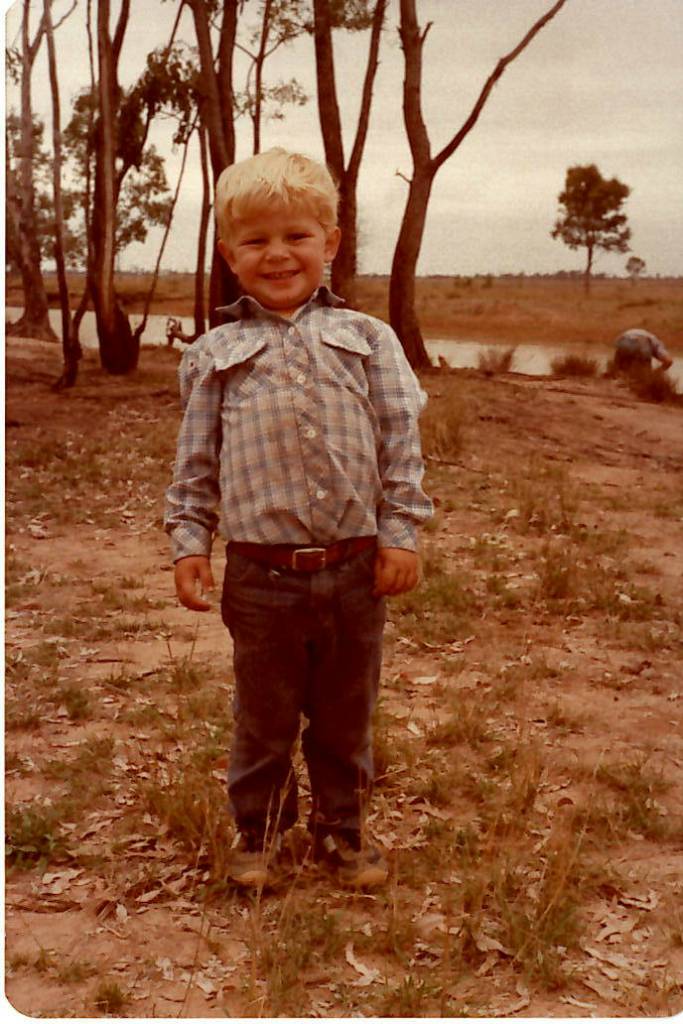

I was never much of a country kid, although it did teach me the fundamental lesson that water is life. Growing up on the farm, you get to observe first-hand the abundance that comes from having enough water. And the death that arrives – of grass, and cattle, and eventually hope – when that water departs.

So you obsess about the weather, and the Southern Oscillation Index, and Indian Ocean Dipole.

Long after moving to the city, my mind still doesn’t make the association of 420 with marijuana, instead that’s the time the Bureau of Meteorology’s afternoon forecast is released.

*****

But it also taught me a deeper truth about power, or rather powerlessness.

Because my dad’s entire livelihood, and our family’s fortunes, depended on something over which we had exactly zero control – whether enough wet stuff fell from the sky. And even whether it fell at the right times.

A reality brutally reinforced when, for the five years I was away at boarding school, the rain stopped falling.

For some of those years, it was six months or more between even the briefest of showers. Some of the stock died, more had to be sold off. There were no crops.

The only reason the business didn’t go under was because of mum’s income from the mine.

It was difficult watching my parents endure that drought, especially from a distance of 800km. But toughest of all was knowing there was absolutely nothing I could do about it.

*****

When I was younger, I drew the wrong lesson from that painful experience.

I used to think that being dependent on the vagaries of the weather was an excellent reason not to be a farmer. And while that’s still true, in my youthful arrogance, or at least naivety, I thought I could instead study, and work, in areas where I would be able to exert control over my own destiny.

It took me until my 30s to comprehend that you can never really have power over your surroundings. No matter what you do, or where you live, you are dependent on so many different things around you that lie entirely outside of your control.

It might not be as black and white (or green and brown) as whether it rains or not, but you have to embrace your powerlessness and just get on and do the best job you can.

I was never much of a country kid, but for a long time that was how most other people perceived me. I suppose that much was unavoidable during my five years at boarding school – especially the first three when I was in the same dorm as my quintessentially rural brother. Even when I was at university in Canberra, however, somehow the metaphorical odour of hayseed and manure seemed to follow me around.

I don’t know that I would say I was ever truly ashamed of it – and certainly not in the same, visceral way I experienced shame about being gay while I was in the closet – but I was definitely embarrassed about my country origins.

For a long time I took deliberate steps to conceal my bush background, making sure to eliminate any hint of a rural twang in my accent, and speaking little about my childhood.

By the time I moved to Melbourne in my mid-twenties, very few people could have guessed I grew up on a cattle property in the middle of Queensland.

I was never much of a country kid, although that didn’t stop me from playing up the fact I grew up on a ‘station in the outback’ to pick up men interested in that kind of thing. A tactic that was particularly successful in my post-Brokeback Mountain North American summer holiday of 2006.

I was never much of a country kid, but I couldn’t escape it even when I worked in politics. As an adviser, whenever I had to go to the Senate chamber from the ministerial wing, I would walk past the National Party Senate Whip’s office.

With the door open, passers-by could see a long scroll celebrating all the people who had ever been Senators for the Country/National Party. About half-way down was my grandfather’s (dad’ dad) name, who served for a decade in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

The fact my grandfather had voted to block supply against Gough Whitlam was a source of much amusement to my first boss there, John Faulkner (an avid historian of the parliamentary Labor Party).

Things became even stranger under my second boss, Joe Ludwig. At the start of the second term, Gillard appointed him Minister for Agriculture. As one of only a handful of Labor advisers who grew up on the land, he asked me to stay on. Suddenly I was Senior Adviser with responsibility for meat and livestock issues, including the cattle industry.

Never in a million years did I imagine, growing up in 1980s Central Queensland perennially dreaming of the day I could finally leave for the city, in my 30s I would end up providing advice on beef policy.

The denouement of my time in politics was perhaps the most bizarre. One of my final responsibilities was to accompany Joseph to ‘Beef 2012’ in Rockhampton.

For those who may be unfamiliar, ‘Beef’ is basically a week-long carnival of carnivorism, held every three years (coincidentally, for a long time one of my aunts was involved in its organisation).

It was the kind of event I spent my childhood desperately trying to avoid being dragged along to. Yet there I was, shepherding the Minister around, showing him the exhibits, introducing him to stakeholders – even to my parents, who had driven up especially for the occasion. Completely surreal.

I was never much of a country kid, or so I had always told myself. My subconscious clearly must have disagreed.

In my late 20s I hit what could be described, in an understated way, as a rough patch. The depression I developed because of that homophobic boarding school had never really left me. My choices for self-medication (party drugs) and self-esteem (seeking to be affirmed through physical desire from others) had, unsurprisingly, not helped either. The breakdown of the first relationship in which I had fallen, hard, was enough to push me to try to end it all. And it nearly did. End.

Apparently, in the suicide note (which I still don’t remember writing) I asked to be cremated and for my ashes to be spread over the farm where I grew up. I guess, deep down, it must have felt like home.

[Dear reader, in case you’re worried, I’m fine now. Better than fine. I managed to draw on the same resilience my mum had shown, and overcome my depression. But please, if you’re considering sending your child to a school that treats LGBT kids as second-class, in any way, just don’t. And that goes doubly so for anti-LGBT religious boarding schools. Thanks.]

I was never much of a country kid, back when I actually was a kid. But from my early 30s onwards – that point in life when you exhale, and stop running from the things you were convinced you needed distance from – I think I become a little bit more ‘country’ with each passing year.

It started with little things, like finding visits to my parents’ farm more calming than constricting.

Or seeing the horses and other animals through Steve’s eyes; independently beautiful rather than creatures of industry.

While the idea of being apart, external to the action, once terrifying, now appeals.

Indeed, nothing confirmed this evolution as much as the first home Steve and I bought – a 2-bedroom, high-rise apartment in inner-city Sydney.

Lots of things went wrong with the apartment, physically, from leaking windows to clogged drains, and even builders needing to rip holes in the walls to fix cracked A/C pipes.

But I wasn’t prepared for it feeling wrong, mentally, as well. Having finally planted roots in the buzzing heart of the metropolis and, well, I wanted to be literally anywhere else. He did, too.

We’ve made some major changes since then, including moving to Wollongong which is both closer to his parents, and further away from the madding crowd.

Somewhat more drastically, we also sold that unit and instead bought our future retirement house… in Queensland (surprising myself, but my mother more).

Sure, it might be closer to one acre than 16,000, and it’s on the Blackall Range of the Sunshine Coast Hinterland rather than having a view of the Blackdown Tablelands.

But it’s big enough for plenty of fruit trees, and has space for a couple of dogs (pets, this time) to roam.

There’s even a chook shed in the back corner (I’m not convinced whether we’ll use it yet, although at least I’ll know what to do).

Oh, and did I mention my parents live on the block next door?

I was always a country kid. Even if I didn’t accept it for a long time, because I couldn’t see myself in the various clichés of what that supposedly entailed.

You would think spending years fighting against stereotypes on the basis of sexual orientation would mean I understood that stereotypes of who is ‘country’ can be limiting and inaccurate, too. Well, I got there eventually.

Growing up in country Australia has influenced me in countless ways I have only recently begun to comprehend, and I’m sure in others I haven’t figured out yet.

I am undeniably a product of those years spent on the land, of the quiet and the isolation.

Obviously of my parents, too: softly-spoken and gentle, but with hidden backbone and not afraid of the argument (which, incidentally, are handy attributes for an LGBTI law reform advocate).

Even though my childhood looked very different to those of my sister and brother, being a country kid is just as much a part of my story as theirs. And I’m finally comfortable with that.

For LGBTI people, if this post has raised issues for you, please contact QLife on 1800 184 527, or via webchat: https://qlife.org.au/

Or contact Lifeline Australia on 13 11 14.

What an absolutely beautiful story. thank you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks very much Tamsin, I really appreciate it!

LikeLike

This is fantastic Al, one of the best posts of yours I’ve read. It’s a fascinating journey to be on, discovering and accepting that parts of ourselves that we spend so long trying to escape. I know my own journey of becoming more like my father has been filled with similar moments of surprising comfort. Funnily enough, I never thought of you as a ‘country kid’ at school, although that’s probably because there were so many egregious stereotypes in our year to contrast you with! I do remember your aggravation at that song “Way out west” though, and the idealisation of country life as being carefree. Anyway, thank you for another great read 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks very much Nick. It’s strange that you never considered me to be a ‘country kid’. I guess I was rejecting that label so hard, from so early on (including to distinguish myself from my brother in the same boarding house), that I fooled even those in the same class! And I agree, the past 10, and especially 5, years has been a really beautiful time of making peace with the past and accepting history that can’t be changed, only learned from.

LikeLike

Hi Alistair,

Thank you for sharing this very powerful and moving essay. I was spell-bound by your vivid prose in depicting the isolation, harshness and beauty of the Australian countryside. But your honesty , candour and openness about life as a kid who didn’t feel like he fit into country life was compelling and deeply touching. Your realisation that your experiences as a country kid has shaped the person you are today is heart-warming. It has made me reflect on my own upbringng in a rural farming community in Northern Alberta as the daughter of immigrants and the only Indian family in the community. The isolation, loneliness and desire for the bright lights of the city led to my rejection of this farming community. I too, have come to the realisation that my experiences in this small rural community have shaped me and made me the person I am today. And that in many ways, I am just a small-town girl from a rural farming community.

Thanks Alistair for sharing. You write beautifully.

Best wishes,

Sandy

From: alastairlawrie Reply to: alastairlawrie Date: Sunday, 29 August 2021 at 6:07 pm To:

Subject: [New post] Never much of a country kidAlastair Lawrie posted: ” I was never much of a country kid, despite growing up outside Blackwater, a couple of hours west of Rockhampton in Central Queensland. Our family lived on 16,000 acres of what I now know is Gangulu/Ghungalu land – a fact never mentioned in my Bjelke-P”

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks very much for your kind words Sandy, I really appreciate it. And I love that our experiences, half a world away, can have so many similarities – and that we are both on the same (sometimes long) journey of self-acceptance.

LikeLike

Such a beautiful post Alastair! I read it twice and wept. You are a beautiful writer.

Also, were you at Drag-Con New York in 2017? I thought I saw you there.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks very much, that feedback is very kind!

And yes, I was actually at NY Drag-Con that year – what a small, small world!!!

LikeLike

really enjoyed this, we have similar backgrounds….my country just happened to be a dairy farm in Missouri – I related to this line the most, ” the lingering effects of that late-primary school drought in conversation, my under-developed communications skills and overly-honed ability to retreat into my thoughts, meant I started at a distinct disadvantage.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks very much for your kind feedback. I really appreciate the fact that someone on the other side of the world can relate to something so personal I wrote about the experience of growing up in Central Queensland.

LikeLike